Closes of the Royal Mile

Closes of the Royal Mile

Edinburgh is not only a historic city, but an ancient one. With over 10,000 years of human settlement, it is appropriate that the oldest surviving building – St Margaret’s Chapel, is indeed its highest elevated, on the top of Castle Rock.

Established as a ‘Royal Burgh’ by King David I in the 12th century, the heart and community of the city, developed between Edinburgh Castle in the north and Holyrood Abbey in the south. Composed of the streets ‘Castlehill’, ‘Lawnmarket’, ‘High Street’, ‘Canongate’ and ‘Abbey Strand’. Deep, steep and snaking down either side of this world-famous thoroughfare, is a network of alleyways or in Scots ‘closes’.

To describe an Edinburgh close is to imagine a narrow, steep path with tall buildings stealing the space and daylight of those venturing below.

The name is believed due to the gates that would secure residents at the top and bottom, or due to the proximity with which neighbours resided. Though the physical character and architecture would change as the centuries rolled by, the characters occupying would remain to live and shape our cities story.

By 16th century, Edinburgh was a thriving metropolis and Scotland’s capital city. With success, the people, confined by the ‘Flodden Wall’, spread down the closes of the Royal Mile and finally into the towering Tenement buildings that would dominate the skyline. By the end of the century roughly 20,000 people would cram within the city walls, living down 300 densely populated closes. Though only a fraction of these remain today: lost to history, town planning and fire. We can imagine the voices of those before.

Now living in such a tight space, to walk through 17th century Edinburgh would bring you into contact with every background and profession. We see hints in the very names of the closes themselves: ‘Borthwicks Close’ named after the Lords of Borthwick Castle who resided here, or ‘Semples Close’ named after ‘Lady Semples’. Names were not only reserved for the nobility, ‘Byers Close’ named after the wealthy merchant John Byers or ‘Chalmers Close’, named after Belt Maker Patrick Chalmers. Robert Milne, ‘Royal Master Mason’ for King William and Queen Mary, gave his name to ‘Milne Court’ on Castle Hill, a close described as embodying the very best in fashionable living of Edinburgh’s thriving centre.

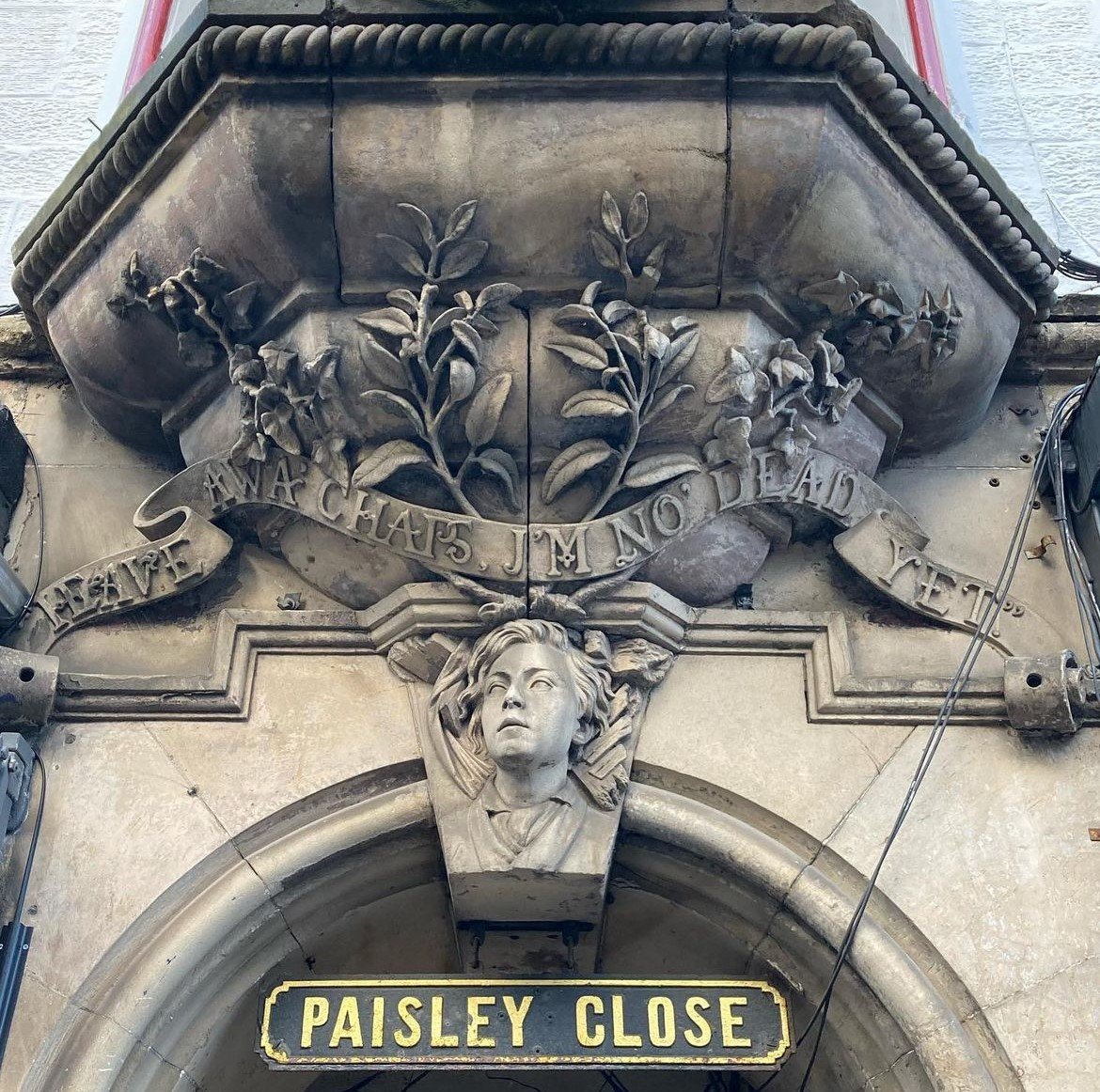

An intriguing clue into the everyday lives of the people of Edinburgh can found on entering Paisley Close. it was here on 24th November 1861 a rotting tenement collapsed, waking the people of the town. A terrible loss of life ensued, though in the rubble were spotted the legs of a young boy. At full pelt he was said to shout “heave awa lads, am no deed yet!” – pulled to safety his words still grace those entering the close today.

Danger was not only reserved to those living in poor accommodation. To venture down ‘Old Stamp Office Close’ in the 18th century, travellers could experience the spectacle of the flying sedan chairs owned by ‘Countess of Eglinton’ and her seven daughters, as they made their way to dances on ‘Old Assembly’s Close’.

Though a very real danger, came in the dreaded cry of ‘Gardyloo’! By mid-18th century, Edinburgh’s population was close to 60,000. Built on rock, the city lacked an adequate sanitation system. Previously, any waste was collected in a bucket and thrown from the window down onto the close and people below. This was to change with the ‘Nastiness Act’, which banned emptying of buckets during daylight hours and required that a warning cry of ‘Gardyloo’, French for ‘beware the water’, be shouted before emptying the contents, whilst always waiting for the reply ‘haud yer hand’ as the good people of the town ran for cover.

Though sanitation would prove a problem for the city, the closes still housed a warren of local and national industries from map making to coin production: South Grays Close, once known as ‘Mint Close’, was the location of the Royal Mint till 1877. These names give us a window into the historic sensory experience of the town. ‘Fleshmarket Close’, named after the meat market located at its southern edge or ‘Old Fish Market Close’ described as ‘a steep, narrow stinking ravine’ sold fish and poultry to the people, whilst adding to the aroma along these narrow, overcrowded passageways.

These smells would have been countered by the countless pubs, brewers and bakers, such as that on the west side of ‘Bakehouse Close’. Today’s Royal Mile focuses on Edinburgh’s booming tourist market from shops to museums: ‘Writers Museum’ located on ‘Lady Stairs Close’, named after famous 17th century beauty Elizabeth Dundas.

It was in the 1930s that a unique industry would develop on Panmure Close, the location for ‘Lady Haig’s Poppy Factory’. Founded to produce the unique Scottish Poppy, to this day the charity still employs veterans to produce these personal memorials to the fallen of Great War.

With so many Edinburghers living stacked and squashed together in the closes, crime for many would not be far away. Indeed, it must be expected that children walking through ‘Old Fish Market Close’ would lift their pace on passing the home of the City Hangman or ‘Doomster’. Of all those to meet such a public servant on the gallows would be William Burke, from the notorious Burke and Hare, who committed their murders in the shadows of the Edinburgh closes, including the tragic murder of Mary Paterson on Gibbs Close in November 1828.

Arguably Edinburgh’s most famous criminal would forever be associated with ‘Brodies Close’. The Brodies, residents here since the early 18th century, were a respected, cultured and prosperous family in city society. Their members were renowned and skilled as: playwrights, lawyers and cabinet makers. Francis Brodie, born in 1708 was elected as a member of the Tower Council as ‘Deacon of the Incorporation of Wrights’, a title he would pass on to his son William Brodie.

William would become infamous for his double life: by day, he pursed a respectable turn as a tradesman, deacon and cabinet maker. By night, he was a housebreaker and thief, using his influential position of trust and status to have access to the homes of Edinburgh’s elite. Brodie would use the spoils of his crimes on women, gambling and ungodly pursuits.

After a failed raid, Brodie would take to a life on the run to the continent before being shipped back to Edinburgh. On 1st October 1788, he was hanged in front of a crowd numbering 40,000 people. Though the Brodie mansion no longer exists, the close where this infamous Edinburgh character lived still bare his name, along with a pub a short walk nearby.

With the 1707 Acts of Union and expansion of Edinburgh’s ‘New Town’ throughout the 18th century, the cramped city could finally spread beyond its historic core. It was the century preceding that the people of Edinburgh and Scotland attempted to expand, not in the lands to the north of the ‘Nor Loch’. Rather expansion would take place some 8000km away on the ‘Isthmus of Darien’ in modern day Panama. The ‘Darien Scheme’ was the brainchild of financier William Paterson and would see the Scots in two expeditions attempt to increase national wealth through establishing a trading colony called ‘New Caledonia’ in the ‘Isthmus of Darien’.

Coordinated through a new trading company called ‘The Company of Scotland’, based off the Royal Mile on Mylnes Square, these failed expeditions would lose as much as half of the nation’s wealth. Without Royal backing, finance was raised from the people of Scotland, with the rich, middle class and destitute keen to chase their fortunes.

Nowhere was this more evident than the closes of the Royal Mile: ‘Milne Court’ would see many of its residents subscribe to these disastrous expeditions. James Byres, who lived in the upper floors of Milne Court was a leader on the second expedition in 1699. Abandoning the colony, Byres narrowly avoided death as he poetically watched his vessel the ‘Rising Sun’ demolished by the sea off the coast of Charlestown, South Carolina as he attempted to flee back to the comfort and familiarity of Edinburgh.

Whilst those lucky few who did manage to return, unwelcome as they were, with failure and national debt positioning Scotland into closer union with her southern neighbour. The closes of Edinburgh would continue to flourish throughout the early 18th century, till enlightenment, expansion of the ‘New Town’ and ‘Edinburgh’s Great Fire’ saw the closes lose their position as embodying the great, cramped cross section that made Edinburgh life unique.

David - Heritage Guides